The Polygon Podcast: Episode 12 featuring Davide Quadrio and Farah Wardani

In this episode, curator Davide Quadrio is in conversation with curator and writer Farah Wardani about contemporary art in Asia and The Polygon’s current exhibition Third Realm.

You can listen with the player above or iTunes, Spotify, and Google Podcasts.

Follow us on Instagram for more content from this episode.

Banner image: FX Harsono, Still from Writing in the Rain, 2011. Episode art: Jompet Kuswidananto, Still from Body of God, 2011. Both images courtesy FarEastFarWest collection

Davide Quadrio is a producer and curator based in China and Italy. He is the founder of the first not-for-profit independent creative lab in Shanghai, BizArt Center, a platform to foster the local contemporary art scene. In 2007 he created Arthub, a production and curatorial proxy active in Asia and worldwide. Quadrio has organized hundreds of exhibitions, educational activities and exchanges in China and abroad. Recent curatorial projects include “Visions in the Making” at the Italian Cultural Center, New Delhi and Zhang Enli at Galleria Borghese, Rome. He has recently produced commissions with Paola Pivi and Tomas Saraceno and he is currently working on several projects for the Gwangju Biennale.

Farah Wardani is currently Assistant Director of the Resource Centre at the National Gallery Singapore and is the Executive Director of the Jakarta Biennale, 2021. She was previously Director of the Indonesian Visual Art Archive (IVAA), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, a centre for digital archive and documentation of Indonesian art, as well as a platform for research. Wardani has also been active as a teacher, writer, curator and art organizer in Indonesia since 2001. Her curatorial work encompasses collaborations with art spaces such as Cemeti Art House, Yogyakarta and ruangrupa, Jakarta, Indonesia, and in 2013, she was artistic director of Biennale Jogja XII Equator #2, Indonesia.

FX Harsono, Disappear, 1998, mixed media, courtesy: Indonesian Visual Arts Archive.

FX Harsono, Disappear, 1998, mixed media, courtesy: Indonesian Visual Arts Archive.

FX Harsono has been a practicing artist for over forty years, and has played a crucial role in the development of contemporary art in Indonesia and beyond. His video, installation, painting and performance works since the 1970s have been widely exhibited. He was a founding member of the movement Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru (New Art Movement) that brought installation art and a conceptual approach to Indonesian art production in the mid 1970s. His artworks speak to the global importance of recovering repressed histories, cultures and identities as humanitarian problems.

Disappear is a response to the silencing of those who opposed or criticised the New Order, Suharto’s authoritarian regime. Harsono has appropriated Panji masks to stage a scene of political oppression.

FX Harsono, Kurban Destruksi, 1997, performance, courtesy: Indonesian Visual Arts Archive.

FX Harsono, Kurban Destruksi, 1997, performance, courtesy: Indonesian Visual Arts Archive.

For his performance Kurban Destruksi #1, Harsono dressed in a suit, representing hegemonic power, and had his face painted to resemble the wicked king Ravana from the Ramayana, a Sanskrit epic well-known in many South and Southeast Asian countries. Masks were placed on chairs, which the artist burned using a blowtorch to represent the people “burned” by the regime. He then dismantled the chairs, symbolic of traditional power structures, with a chainsaw.

FX Harsono, Memori Tentang Nana (Rewriting the Erased), 2009, multimedia installation, courtesy: Indonesian Visual Arts Archive.

FX Harsono, Memori Tentang Nana (Rewriting the Erased), 2009, multimedia installation, courtesy: Indonesian Visual Arts Archive.

More recently, Rewriting the Erased is a video performance and installation in which Harsono is seen at a desk, writing out his name repeatedly in ink on paper. The gesture alludes to the fact that from 1967 to 2002, ethnic Chinese Indonesians were not allowed to speak or write Chinese, were prohibited from celebrating traditional Chinese holidays, and had to adopt a Bahasa Indonesian name if they were to remain in the country. Harsono’s act is a symbolic reclaiming of this right.

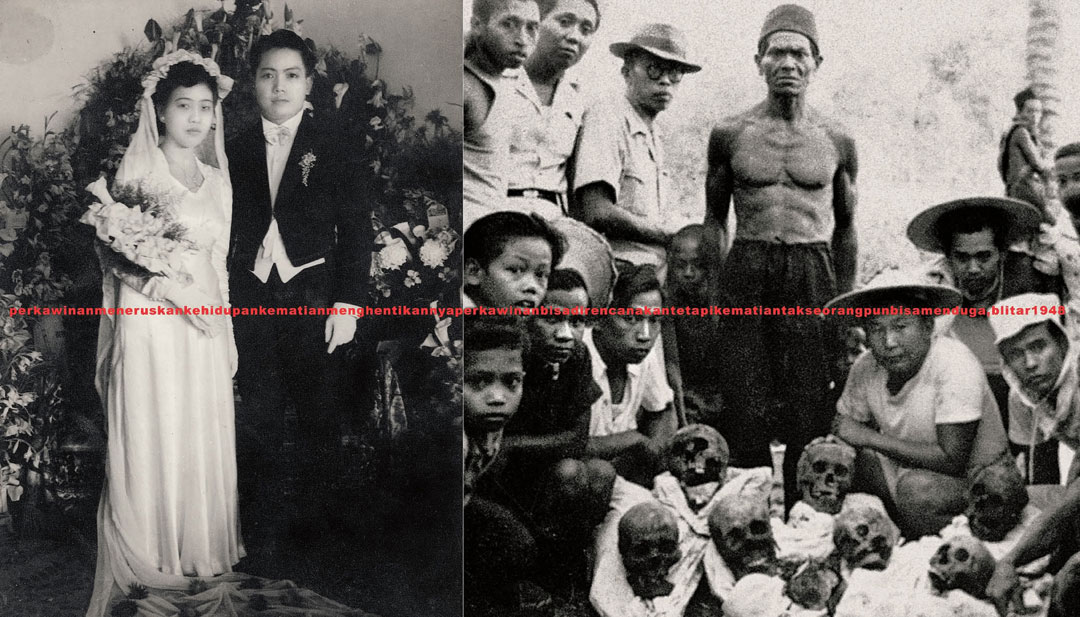

FX Harsono, Memelihara Hidup, Menghitikan Hidup, 2009, oil, acrylic, and thread on canvas, courtesy: Indonesian Visual Arts Archive.

FX Harsono, Memelihara Hidup, Menghitikan Hidup, 2009, oil, acrylic, and thread on canvas, courtesy: Indonesian Visual Arts Archive.

The title of the work Memelihara Hidup, Menghentikan Hidup translates as “Sustaining Life, Stopping Life”. The two diametrically opposite images depict different sides of Chinese Indonesian experience in Blitar from 1948: the wedding of the artist’s parents, and the excavated bones of those massacred at the end of the Indonesian war for independence.

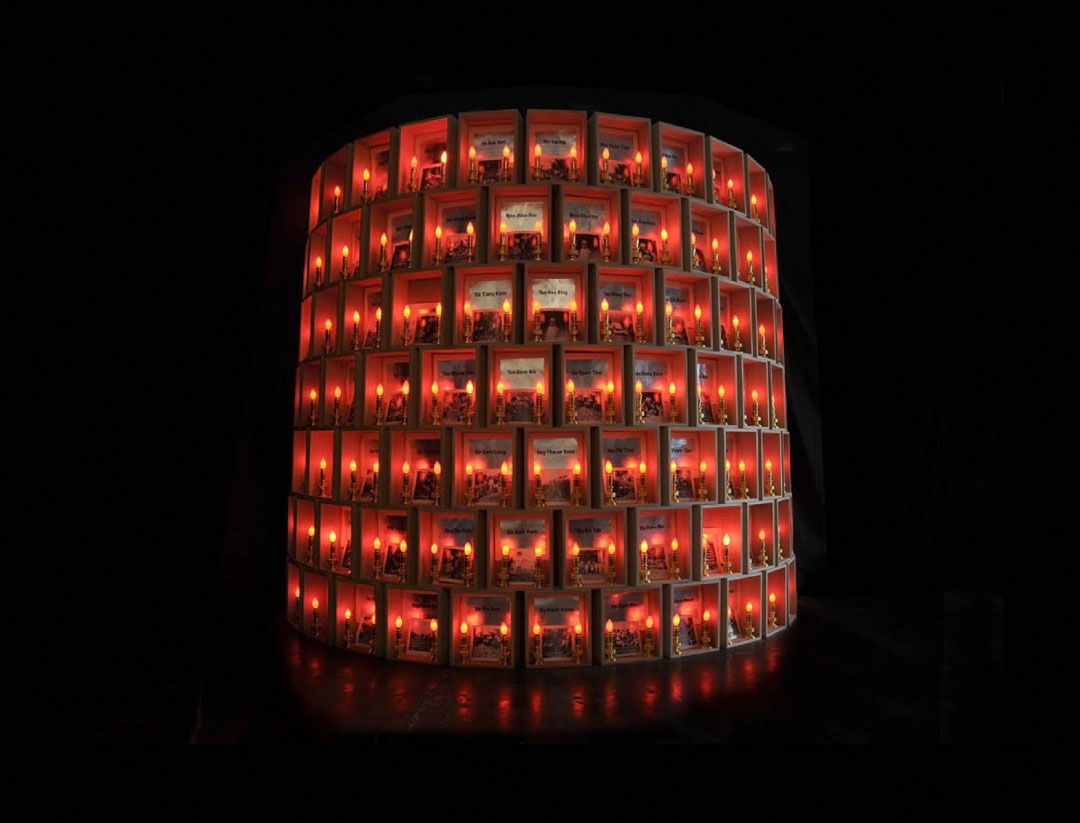

FX Harsono, Monumen Bong Belung, 2010-2011, mixed media, courtesy: Indonesian Visual Arts Archive.

FX Harsono, Monumen Bong Belung, 2010-2011, mixed media, courtesy: Indonesian Visual Arts Archive.

Hundreds of Chinese Indonesians were the victims of robberies and mass killings from 1947-1949 in Blitar. They were falsely accused of collaborating with the Dutch. Monumen Bong Belung, the title of which means “Bone Cemetery Monument”, is an assemblage of small altars resembling a columbarium, commemorating – and, when possible, identifying – these victims of persecution.

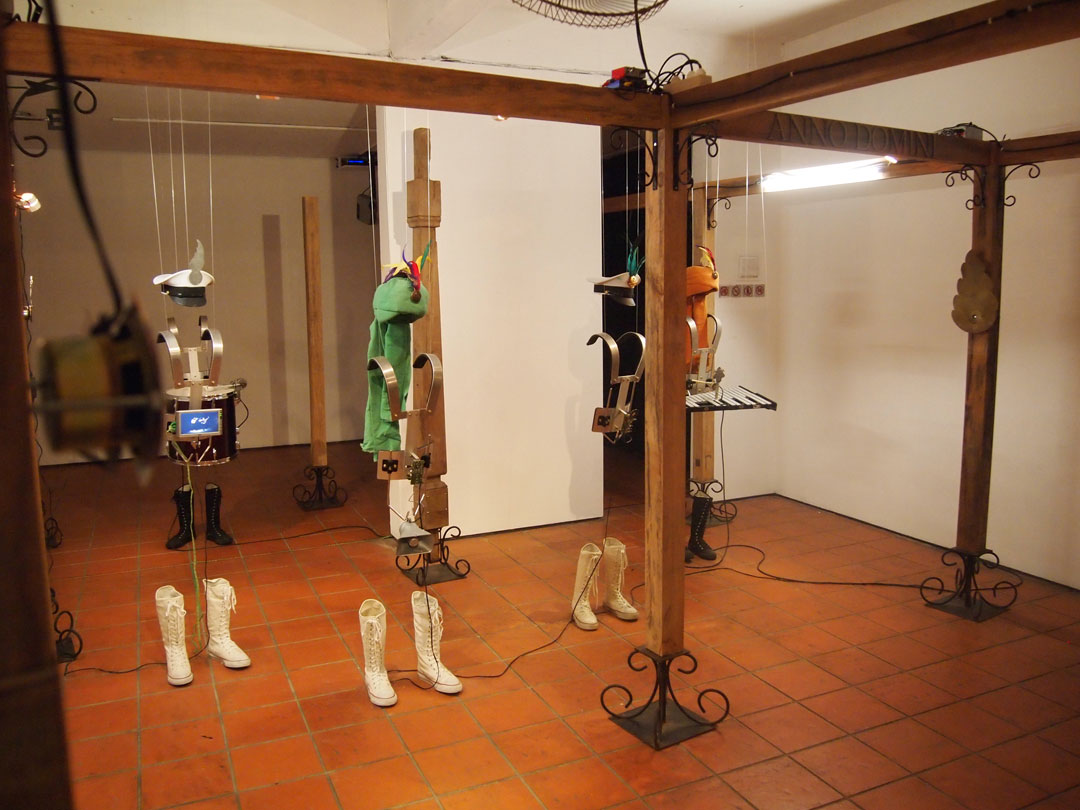

Jompet Kuswidananto, Anno Domini, 2011, mixed media, courtesy: Indonesian Visual Arts Archive.

Jompet Kuswidananto, Anno Domini, 2011, mixed media, courtesy: Indonesian Visual Arts Archive.

Indonesian artist Jompet Kuswidananto works across a diverse range of mediums including installation, video, sound, performance and theatre. Trained as a musician, his multimedia installations often combine video, sound, and mechanized elements. His practice focuses on issues of politics, colonialism, and mass mobilisation in the context of post-reformation Indonesia. Many of his projects are realized through multidisciplinary collaborations. For over a decade his work has been included in many significant biennales, with solo exhibitions across Asia and Europe, including Third Realm at the 54th Venice Biennale.

Jompet Kuswidananto’s Anno Domini visualises the fluidity of culture in Indonesia, interrogating the nation’s history of unsettled transition. Here, disembodied military uniforms are suspended, with hardware and costume elements that allude to both contemporary and more traditional identities.

Jompet Kuswidananto, War of Java: Java’s Machine, 2008, mixed media, courtesy: Indonesian Visual Arts Archive.

Jompet Kuswidananto, War of Java: Java’s Machine, 2008, mixed media, courtesy: Indonesian Visual Arts Archive.

Java Amplified and War of Java: Java’s Machine continue Jompet’s interest in identity, critiquing the notion of cultural purity. In his Java series, he references the impacts of Dutch colonisation on Javanese culture, while highlighting other ethnic and religious traditions that were influential long before colonialism. Jompet’s work suggests that all cultural identities are hybrid and syncretic.

Jompet Kuswidananto, Cortege of the Third Realm, 2011, mixed media, courtesy: Indonesian Visual Arts Archive.

Jompet Kuswidananto, Cortege of the Third Realm, 2011, mixed media, courtesy: Indonesian Visual Arts Archive.

and the social imagination. In Cortege of the Third Realm, in-between or transitional identities are likened to the “third realm” of Buddhist cosmology, in which there is no physical form. The robotic components of Jompet’s installation are laid bare, out of time with the ceremonial and historical uniforms.

Subscribe to The Polygon Podcast on iTunes, Spotify, and Google Podcasts.